How Much Is Enough?

On Morrissey & Marr

This will be the first essay I’ve written about Morrissey in over ten years. In the future I once envisioned for myself, the general idea was to never write about Morrissey again. I’d said everything I had to say. I was moved on. I started writing about other things.

But here we are.

The last time I gave an academic paper on Morrissey was at a conference in Limerick, Ireland in 2009, I think. I was testing out a new idea. That Morrissey’s fans enabled him to say racist things through the sheer intensity of their loyalty and devotion which shielded him from public criticism.

It was, shall we say, not a popular theory.

I was speaking at an academic conference on Morrissey and many of the other papers that weekend were intense and scholarly examinations of Morrissey’s unique genius and unquestionable greatness. It wasn’t supposed to be a fan conference. But even in academia, wherever Morrissey is concerned, nothing is ever guaranteed. I’ve faced tough rooms before—at conferences and in the classroom—but after I’d finished laying out my case why excessive loyalty can prove to be a bad thing with harmful consequences (to the person to whom you’re being loyal), I wished I’d had the foresight to hire personal security, because it wasn’t one hundred per cent that I was it making it out of the lecture theatre unscathed.

That was the one of only a few times I’ve said explicitly critical things about Morrissey to an academic audience—before or since. They were very unusual occurrences in a 20-plus year career during which my major accomplishment was to find ways to sing the praises of Morrissey all the time—even when I wasn’t talking about Morrissey. My academic journey or odyssey or death march from hell now mercifully ended, began at the age of 28—me having made (this is fun, I get to use Smiths’ lyrics again it’s been so long) “a terrible mess of life”. It continued almost entirely because in Communications Studies I found out pretty quickly that I could write about The Smiths and Morrissey to my heart’s content, and, if I got good enough, travel the world and make a career out of what had always been my lifelong obsession. Friends, colleagues made fun of me all the time to my face, behind my back, sideways, and down low—all the ways Smiths fans always suffer: “Oh my god, look at him, he has a Morrissey pompadour AND he’s talking about Morrissey. Don’t laugh, you’ll make me start.” That sort of thing.

I didn’t care. Well, I did care when I found out. But that was years later. Then, I was living the dream life of a lifelong Smiths fan.

For the benefit of new readers joining us, and to explain how far Morrissey and me go back, let me rewind a bit. In 1988, I was expelled from the prison-like Christian boarding school in South America, where I was held while my parents spread God’s love in a different country. I was sent to live with foster parents in Calgary, Alberta. It was a frying pan to bonfire sort of situation. The trauma of those years followed me for a long time. It might well have killed me then if I hadn’t discovered a record called Viva Hate. It is not an exaggeration to say that this single product, this specific commercial purchase, changed my life forever.

When I arrived in Calgary, I was a Chilean kid with a Canadian passport and an American accent. I had become a type of invisible and unclassifiable immigrant. “My” country felt more foreign to me than any other place I had ever known. The suburbs were so ugly I didn’t understand how people could stand it.

Morrissey made all of this bearable. Simply knowing that Morrissey existed was enough to make me want to continue existing as well. He was the first man I’d ever heard who didn’t seem to me to be talking complete and utter nonsense. The men of my dad’s age, the men of Morrissey’s dad’s age—at least in the English-speaking world—were made rancid by their bad readings of masculinity. In that old man’s world, the worse you treat your children, the more it means you love them.

Let’s work in a second Smiths lyric right about now, just do it:

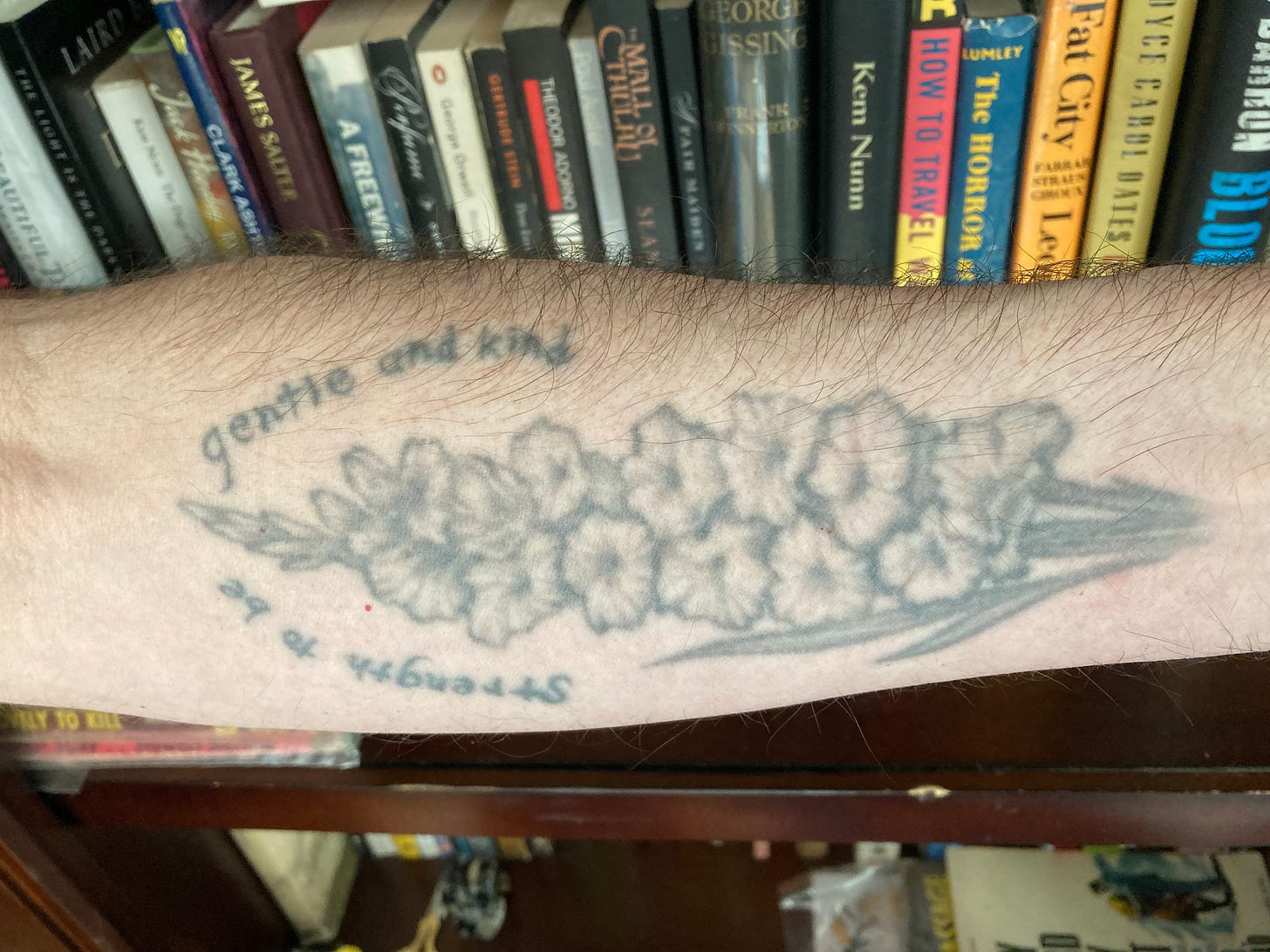

“It takes strength to be gentle and kind”

I’d never heard any man advocate those virtues before.

Give or take Jesus.

But every single man in my life—one or two possible exceptions—who professed their love for a gentle Jesus turned out be vindictive, merciless, and unforgiving. Always in the name of Jesus.

Morrissey meant it.

You could hear it in his voice. You could feel it in his words.

All of this to say, the major perk of being an academic for me was not the salary, not the tenure, not the travel. I really just wanted to spend my whole life hanging out in my head with Morrissey. Becoming a professor was just changing my status from amateur to professional.

At first it went way better than I could ever have expected. An academic abstract of mine found its way to Chuck Klosterman, then at SPIN Magazine. Klosterman had heard something about Morrissey being big with “Latinos” in L.A. Impossible as it now seems, in 2002 I was the only one out there writing about Morrissey and Latinos. It didn’t seem strange to me. Although I was a Canadian in Canada, I was also a Spanish-speaking Chilean who’d felt a connection to Morrissey that seemed to be addressing itself to Latin side of me. The last time I was in Santiago was in 1989. Everyone I knew could sing the chorus to “Everyday is Like Sunday” even though they: a) didn’t know what the words meant; b) didn’t really care either. Maybe there is no answer and there never needed to be one to begin with. Something about Morrissey’s voice and the melody of certain songs, hits a lot of Spanish-speaking people like an automatic bullseye to the heart.

To pick up where I began, back in Ireland 2009, my thesis that Morrissey’s racism was sliding into new territory that might cause him some trouble down the road was so novel that, honestly, the look on the faces of some of those Morrissey fans/academics that day, it was like I’d just Judased them right to the junk, like I’d crossed over into unclean territory and there was no coming back for me.

Yet here we are in 2022 and the situation is entirely in reverse. If there were a Morrissey conference this upcoming Fall, all of the papers would be critical of Morrissey. If I dusted myself off the shelf, wrote a positive paper on Morrissey, submitted a decent abstract, got accepted and showed up to give my paper I think people would scream at me, interrupt me, call me a Nazi enabler, tell me I was causing them actual harm. Newspapers would report that a fascist agitator had infiltrated a normal and peaceful Morrissey Is a Racist conference, and that courageous participants had acted quickly to quell the violence.

I hope and pray I never have to speak at an academic conference ever again.

But if I was forced to publish a final paper on Morrissey I’d argue that I no longer find the arguments against Morrissey compelling enough to justify continuous persecution. I’d argue my overall impression of Morrissey as an artist and public figure—considering the whole body of his recorded work and accessible public utterances—was that he seemed a fundamentally decent human being whose incessant flogging in the public square has turned into a gruesome and inhumane spectacle far worse on a moral scale than anything Morrissey has ever said or done.

Matt Berninger of the National, himself a big enough fan of Morrissey’s solo career to namedrop the album name Bona Drag elsewhere in his oeuvre chastises himself for lacking the courage to “punch a Nazi.”

The lyric appears on the song “Not in Kansas” from the 2019 record I Am Easy to Find. 2020, what with the U.S. election and all, was the peak year for wanting to punch people with whom you had political differences. 2019 was a brutally bad year too in the old tolerance department. Punching people wearing red hats with the word “great” on them was considered an act of exceptional moral virtue by all good people who called were of the “left.”

Now, don’t get me wrong: if Hermann Göring, in some reanimated, nightmare apparition—still sporting his handsome Boss-made Nazi uniform—shows up at my door delivering a package from Amazon, then yes, I’m going to fucking punch that Nazi, Matt, and you should, too. Uppercut the shit out of ol’ undead Hermann, it’s the right thing to do. But, Matt, if you’re talking about punching the butcher from whatever small Ohio town I’m presuming at least one of your grandparents, probably, must have come from, I’d say don’t punch him.

People everywhere are poor, frightened, and confused. They’re also human. Humans experiencing those emotions feel anger. Shit tons of it, too. Angry humans make mistakes—especially when they’ve been fucked over by a corrupt corporate-political class going back generations now. There is no virtue in punching scared, poor, and confused people—no matter how angry they become. No matter what they believe.

It's actually kind of sick and disgusting when you get right down to it. Maybe not the first punch, Matt. The first punch, I don’t know, maybe it’s necessary to get your “Nazi” butcher’s attention. I get it. He deserved one good solid pop. Fair enough. But the second, the third, the three hundredth? What kind of evil delusion does a society have to be operating under to imagine there’s virtue in that? If, in 2009 I had been able to foresee the utter lack of nuance with which the new authoritarian left silences discourse and shames all dissenters, I would not have delivered that paper.

I have not listened to any of Morrissey’s records since 1997’s Maladjusted. I don’t know the guy at all, I don’t want to meet him: I just want to say that enough is enough.

Morrissey didn’t kill anyone with drones.

Morrissey didn’t kill anyone with failed drug polices that didn’t work.

Morrissey didn’t make you waste your life getting dumb on social media.

Morrissey didn’t blow up a stadium or a mosque or a temple.

Morrissey is not the mastermind behind the NRA.

Morrissey does make extremely questionable decisions in the pants department these days, but if we’re shame-targetting people for pants now we’d have to roll things back and apply retroactive justice to MC Hammer and see where it goes from there. Things could get ugly. Not as ugly as Morrissey’s pants, but still—pretty bad.

I was extremely dismayed by Johnny Marr’s sneeringly dismissive Twitter response to an open letter Morrissey had posted on his web site a few days earlier.

(As always these days, I’m writing by hand with no internet, so instead of elaborating further on this sequence of events, I’d just suggest you do a News search for the general gist of their quarrel.) Just before I got back to these notebooks, I’d been on a prolonged Dick Cavett expedition on YouTube. Cavett, for the unfamiliar, was an American talk show host, regarded by many, me included, as the best of all time. Like by an embarrassing margin for everyone who has come since. Kirk Douglas was on and Cavett kept trying to make Douglas say something nasty about John Wayne. John Wayne and Kirk Doulas were, to understate the frosty nature of their famously adversarial relationship, on opposite sides of the political spectrum. Throughout the House Unamerican Activities Committee (HUAC) hearings of the 1950s, Wayne was among the loudest voices denouncing all commies as traitors and arguing that ratting them out was every American’s patriotic duty. Douglas, on the other hand, believed in free speech and the right to peaceful assembly. Hollywood Communists hadn’t done anything. The U.S. is a free country—that kind of subversive thinking. Turning in your friends to the authorities is not a virtue. Douglas refused to take the Cavett bait.

What he said was that he’d worked with John Wayne, that he’d never seen a more professional actor in his whole career, that he was exceptionally dedicated to his craft and that he worked harder than anyone he ever knew. He said that there were lots of issue where he and John Wayne didn’t see eye to eye, but that working with him was a pleasure and he was proud he’d got the opportunity.

To me it seems that if Kirk Douglas can see the good in John Wayne it’s one of the saddest indicators of the abysmal, actually quite dangerous level, of public discourse of the present era, that Johnny Marr doesn’t even have it within himself to say something like,

“I haven’t agreed politically with a single thing that’s come out of Morrissey’s big mouth since way back when I was beach buddies with Bernie Sumner, but he is the best songwriter of his generation and he made me what I am today. So, I mean, I’d be a right asshole if I slagged him off now, innnit?”

I know people from the North probably don’t say, or even think, innits. But it’s, I don’t fucking care, innit?

Johnny Marr’s response doesn’t have an ounce of gentleness or kindness in it.

This weekend my writing was interrupted by a couple steady hours of really loud honking from the street outside. I looked out and saw big rigs going both ways through the city, leaning on their horns and a lot of them flying the maple leaf upside down. I have been on a news blackout for a month now, and I did not know what was going on. I asked my partner. She told me it was Canadian truckers protesting having to get vaccinated to go across the border.

I said and I quote, “Makes sense to me.”

My partner nodded then said, “But online, everywhere and everyone is denouncing them as racist and saying not to support them unless you too are racist.”

This I don’t get.

What does the one have to do with the other?

Even if 100 per cent of all of the truckers in Canada—the Sikhs, the Muslims, the Albertans, the Mexican-Canadians, the Newfoundlanders, the Sudanese-Canadians—were all secretly thinking simultaneous racist thoughts about each other all the time, what does that have to do with their right to exist, to find employment to feed their families, and to protest the conditions of their employment or against the government or any other cause of their choosing—either as individuals or as part of a broader movement?

Thought—no matter the thought—is not a crime.

If five truckers of any sex, ethnicity, age, or religion have a BBQ in one of their own backyards and one of them tells an inappropriate and ethnically stereotyped “Three guys walk into a bar…” joke no law has been broken and no hate speech has been committed.

Sure, those jokes are cheap, hurtful and I wish people didn’t tell them. So what? People say all sorts of things I wish they wouldn’t. That’s what a free society looks and sounds like. A racist joke causes greatest harm to the idiot who tells it. It reflects poorly on them. No further punishment is required for those who punish themselves every second time they open their own mouths.

Which brings us back to Morrissey.

Whatever he’s done and said, his sentence has been served.

It’s over.

Leave him alone already.

Johnny Marr, if Kirk Douglas can see the good in John Wayne, and you can’t find it in your heart to refrain from punching Morrissey who made you when he’s down, then of the four legends mentioned in this sentence, you are the smallest one by far.

To the extent that my early criticism of Morrissey may have created the conditions for an indefinite pile-on where vicious cheap shots are welcomed and treasured, I wanted to write and say that I am against it. I’m sorry. I didn’t anticipate the present madness.

In my own strange way,

Colin Snowsell

Vancouver, Canada

1953-2022

Really appreciated this section:

“Morrissey didn’t kill anyone with drones. Morrissey didn’t kill anyone with failed drug polices that didn’t work.

Morrissey didn’t make you waste your life getting dumb on social media.

Morrissey didn’t blow up a stadium or a mosque or a temple. Morrissey is not the mastermind behind the NRA.”

Anger and protest and call to change should be directed at those who are responsible for enforcing the system: government, politicians, corporations - the real crooks. Not to let individuals off the hook for being idiots, but why not target the source? Which isn’t Morrissey, or the trucker convoy. Mere distractions.